A team of scientists witnessed an astronomical

incident seen for the first time in history:

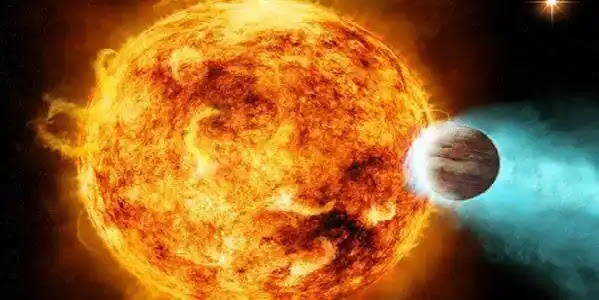

A red giant star devouring a planet, according to

their claims, they witnessed the “future of Earth”

While this phenomenon has long been theorized, finally seeing it in action will help astronomers figure out what happens to a planetary system when the star enters its dramatic death throes, swelling to hundreds of times its original size and swallowing everything in its path before ejecting its outer material and collapsing into a glowing stellar remnant.

Previous observations have captured the stages just before and just after one of these planetary engulfments, but this is the first time the act has been seen, just 12,000 light-years from Earth.

The explosion lasted approximately 100 days, and

features of its light curve, as well as the ejected material, gave astronomers

insight into the mass of the star and its engulfed planet.

There, a star rapidly increased in brightness by a factor of 100 before quickly fading, glowing with an excess of bright, long-lasting infrared light.

This agrees with models describing what will happen at the end of the Sun's life, and provides information that scientists can use to build more detailed end-of-days predictions for our little corner of the Milky Way .

The “future of the Earth”

Kishalay De, an astrophysicist at MIT 's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research , said in a statement:

“We are looking into the future of Earth. If some other civilization were to watch us from 10,000 light years away as the Sun swallows the Earth, they would see the Sun suddenly brighten as it ejects some material, then form dust around itself, before returning to its original state.”

The death of a star like the Sun is a pretty wild process. Observations of other stars in the Milky Way at various stages of their lives have shown us how it unfolds.

As the star runs out of hydrogen fuel to burn in its core, the delicate balance between the outward pressure of fusion and the inward pressure of gravity begins to unravel.

The core begins to contract, drawing more hydrogen from the outer layers of the star toward the center, concentrating it in an envelope around the core. Due to the heat and pressure, this hydrogen shell begins to coalesce, generating additional heat that inflates the outer layers of the star to hundreds of times their original size.

But the outer layers, darker than before, cool towards the reddest end of the spectrum. This is known as a red giant.

The star will swallow anything in the path of this expanding outward material. Here in the Solar System, this process is expected to occur in a few billion years, and the Sun is predicted to expand to the orbit of Mars, swallowing Mercury, Venus and Earth along the way.

Kishalay De. and his colleagues didn’t set out to find

a dying star that would eat its planets. Kishalay De. were examining data

collected by the Zwicky Transient

Facility , which studies the sky in optical and infrared wavelengths, looking

for binary stars in orbits so close that one absorbs material from the other, a

process that generates bursts of light.

Planetary engulfment will cause the Sun to devour

planets in our solar system, study suggests.

What they found was something completely different.

Kishalay De. explains:

“One night I watched a star multiply 100 times over the course of a week, out of nowhere. It was unlike any stellar explosion I had ever seen.”

They found more “oddities” in the star

A closer look at the object's chemical composition, conducted using data from the Keck Optical and Infrared Observatory , revealed more oddities. The star showed signs of elements, such as titanium oxide and vanadium oxide, more consistent with a cold environment, not the hot hydrogen and helium one would expect from plasma-exchanging stars.

Further observations with the Palomar infrared observatory confirmed this. Whatever was going on with the explosion, dubbed ZTF SLRN-2020, it wasn't a binary star, which meant the explosion had to be something else.

A look at the scientific literature showed that the way the light bloomed, died and remained as cool material glowing in the infrared was consistent with a type of explosion known as a red nova, the result of a binary star collision.

But the energy produced was much, much less than you'd expect from a red nova; about a thousandth of the energy, in fact. And that was the final piece of the puzzle.

Kishalay De. said:

“That means whatever was merging with the star must be 1,000 times smaller than any other star we’ve seen. And it’s a happy coincidence that Jupiter’s mass is about 1/1,000th the mass of the Sun. That’s when we realized: it was a planet colliding with its star.”

swallowed planet

According to the team's analysis, the planet would have a maximum mass of about 10 times that of Jupiter, being engulfed and falling towards the core of an expanding red giant.

As the star swallowed the planet, its expanding outer envelope continued to cool, forming a dust cloud around the star that provided the long-term infrared signature observed by the Palomar Observatory.

According to the researchers, this constitutes a “missing link” in our understanding of the evolution of planetary systems.

They call this type of phenomenon “subluminous red novae,” and believe that ZTF SLRN-2020 can help us understand the effect that planetary engulfment can have on the brightness, chemical composition, and rotation speed of late-stage stars.

They estimate that subluminous red novae occur between

0.1 and several times per year. Now that we know what they might look like, we

may find many more.

From the states:

“For decades, we’ve been able to see the before and

after. The before, when planets still orbit very close to their star, and the

after, when a planet has already been swallowed and the star is gigantic.

What’s missing is to capture the star in the act, when a planet suffers this

fate in real time. That’s what makes this discovery really exciting.”

.jpg)

0 Comments