After initially detecting tremors assumed to be

generated by the cooling of Mars' innards and volcanic activity, NASA's InSight

Martian lander has now discovered meteorite strikes. Despite the small size of

the space rocks that have been dropping nearby, InSight is so sensitive that it

has been able to detect seismic waves from collisions up to 290 kilometres (180

miles) away. Now, NASA has released the sound of meteorites striking Mars.

The atmosphere of the Earth is routinely bombarded

by particles as small as sand grains and as large as enormous rocks. These can

create breathtaking sky displays, but only the larger ones actually touch the

earth as opposed to bursting into flames as they descend. On Mars, the

atmosphere is significantly thinner, allowing for far greater object passage.

But being aware of this and actually perceiving it are two different things.

Despite years of Martian rovers and landers, none of them had ever experienced

the seismic waves brought on by an incoming space rock.

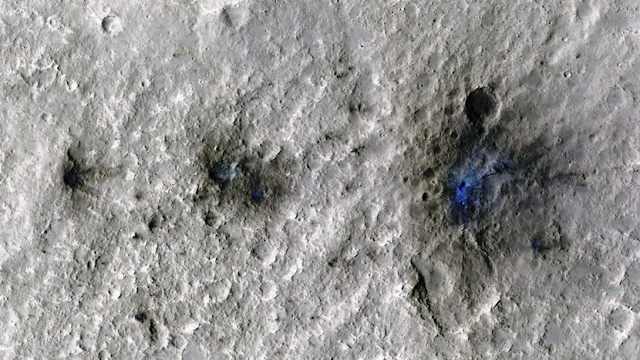

Although InSight has been on Mars since 2018, it

wasn't until an incident on September 5, 2021 that scientists first saw seismic

waves from an impact, as is now documented in a recent publication. But the

wait was worthwhile. The meteoroid exploded due to considerable friction that

was produced even by the weak Martian atmosphere. Not just one, but three

darkish marks left behind by the object after it disintegrated were spotted by

NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

Dr. Ingrid Daubar of Brown University said in a

statement, "It was quite exciting." "The pictures of the actual

craters are my favourites. Those impact craters became stunning after three

years of waiting."

Daubar and co-authors explored further after

determining InSight is capable of detecting the seismic waves from meteorite

impacts. Re-analyzing InSight's historical data, they discovered three less

significant occurrences from 2020 and early 2021. Each produced seismic waves

that were less than a Marsquake of magnitude 2.0.

In three instances, InSight also detected the

object's auditory wave as it passed through the atmosphere. One detection was,

perhaps by coincidence, only five days away from the impact that initially drew

their notice.

Planetary scientists are interested in the craters

for reasons other than aesthetics. All other mission-related data is calibrated

by knowing the exact position of the source of the impacts, according to

Daubar.

The location

and magnitude of the consequences are "validated by this," according

to our estimations. Additionally, it will make it possible for researchers

using InSight's data to more precisely detect upcoming collisions.

Daubar and his associates were perplexed that

striking space objects hadn't been discovered earlier. Mars should meet more

asteroids due to its proximity to the asteroid belt compared to Earth, which accounts

for its smaller size. Although the Red Planet is less seismically active than

our own, InSight has already recorded 1,300 Marsquakes, which previous Mars

landers may not have been sensitive enough to record.

The authors speculate that InSight may have actually

detected seismic waves from previous meteorite impacts, but that these may have

been incorrectly interpreted because the crew wasn't aware of the waves'

particular structure. Now that there are four confirmed incidents, they are

hoping to discover more.

The age of the Martian landscape may be determined

by measuring the frequency of crater-forming events, which enables us to

determine how long craters like this last before being covered by sand or other

processes. Dr. Raphael Garcia, the study's principal author from France's

Institut Supérieur de l'Aéronautique et de l'Espace, explained that impacts

serve as the solar system's clocks.

Ironically, the InSight/Reconnaissance Orbiter

partnership outperforms all of our numerous Earth-based seismic satellites and

equipment. The seismic and infrasound detections from the meteorite's passage

through the atmosphere have only been matched to one crater on Earth. Numerous

hits have been detected by the seismic network set up by the Apollo astronauts,

but none of them have been linked to recently produced craters.

.jpg)

0 Comments